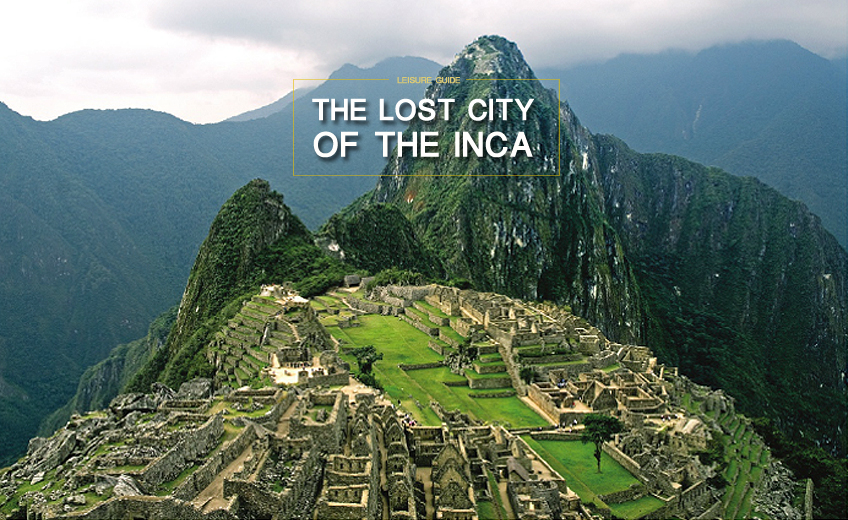

We walked for days over and around some of South America’s most stunning and inaccessible mountains. We walked as the Inca did, step by step towards a mysterious destination that has captivated the world since 1911. After one final ascent of a massive wall of stacked and broken granite, we passed through Intipunku, the Sun Gate, and stood motionless staring down at the cloud-shrouded enigma of the Inca. We had arrived at Machu Picchu.

The effort, the pain, the magical moments all faded from my consciousness as I breathlessly marvelled at the small collection of stones nestled in the saddle between two peaks of a narrow ridge. What was this place? Why was it here? Who were the people that built it?

Our journey to the fabled lost city started on a beautiful spring day in the Andes. My wife and I set out from camp near the train depot at kilometre 88 to trek the Inca Trail with seven other tourist-trekkers, our lead guide Narcico, 15 Peruvian porters and a fabulous cook. The trail is a collection of ancient Inca footpaths interwoven with recently cut connector trails that meander through densely forested foothills in the shadows of snow-covered peaks.

We left camp at around 8am and soon encountered a group of children playing at an ancient archaeological site along the trail. In the shadow of this small cluster of Inca ruins several men worked in the dusty soil. Today the Inca of legend are gone but their descendants continue to farm the Peruvian highlands as waves of tourist trekkers pass silently.

But while the ancient Inca were a privileged and wealthy people, their descendants in the highlands are among the poorest in modern Peru. Many of the challenges that faced the Incas continue to put pressure on subsistence farmers in the Peruvian Andes. Erratic rainfall, difficult terrain and microclimate variations threaten the annual crops of potato and other tubers that have sustained these communities for centuries. It is estimated that up to 60% of preschool children in the highlands suffer the effects of malnutrition.

Two beautiful young girls approached Narcico as if he were a familiar uncle. He reached into a small pouch and gave each of the girls a small piece of chocolate. They were different from the children I had encountered in Cusco and Lima who were rambunctious and excited. They sat among us quietly, with a graceful innocence as Narcico gave us our first introduction to the stones of antiquity that are their modern playground. As we walked deeper into the mountains, we encountered fewer and fewer people. After our second day on the trail the only signs of a human presence were the ruins of a once-mighty civilization.

The Inca Empire was formed during the reign of Pachacútec Yupanqui, who conquered and united other Amerindian nations in the 15th century. In little more than 50 years, Inca influence was extended from what is now Colombia in the north to present-day Chile in the south, with the bustling city of Cuzco as its capital. The united tribes of humble Andean farmers who called themselves the “Children of the Sun” shared knowledge of textiles, irrigation and building techniques to form an advanced and highly structured society … until the old world and the new collided in 1532.

In November of that year, retired Spanish army captain Francisco Pizarro led 62 horsemen and 106 foot soldiers into the heart of Peru. Pizarro and his men were not professional soldiers on a mission of conquest; they were adventurers with a lust for fame and fortune. They were, however, armed with the latest technologies of war, which allowed them to surprise and kidnap Inca ruler Atahuallpa.

The primitive guns and steel rapiers, honed through centuries of war in Spain, certainly gave them a military advantage, but by the time Pizarro encountered the Inca, they were already weakened by a bitter civil war and suffering from the devastating diseases spreading south from European settlements in the Caribbean and Central America. With their royal prisoner issuing orders from captivity, and aided by non-Inca ethnic groups, this small group of foreigners exploited the ensuing chaos and seized control of the empire.

The trail we now follow to the lost city was constructed by extending the extensive stone road network that has traversed the mountain landscape of the Andes for over 400 years. The Inca used these trails to control their empire by moving troops and relaying messages via runners, and as the trade routes to transport goods with llamas and alpacas.

For four days I was consumed by the changing and untamed landscape, insisting to myself that I pause, even briefly, from the constant grind of the trail to witness the beauty that surrounded me. Each evening we arrived at a new camp to find our tents set and dinner cooking. We slept in peaceful silence and rose with the rising sun. The trail is restricted to 500 hikers per day. We rarely encountered anyone. I was surprised to find ruins and evidence of ancient life scattered throughout the Peruvian highlands. We were beginning to understand how Machu Picchu may have fit into the story of the Inca Empire.

It is believed by many that Machu Picchu was a royal retreat for Inca nobility in Cuzco, built during the reign of Pachacútec, a place of spiritual and ceremonial significance, or possibly the administrative centre for a well populated region. It would have been no more than a small town by Inca standards; home to less than 1,000 people at its peak. It is still a mystery as to why the Spanish never found the hidden jewel of the Andes. Some believe that it was abandoned and its memory lost even to the Amerindians of the region before the conquistadors arrived. The entire mountain masterpiece was built, settled and abandoned in less than 100 years. We may never know why.

When Yale professor of history Hiram Bingham stumbled upon the jungle-covered ruins at Machu Picchu in July 1911, he was actually searching for the legendary lost city of Vilcabamba. Vilcabamba was a remote mountain refuge created for fleeing Inca nobility as the conquistadors made their way south into Cuzco. Bingham was looking for the last stronghold of a conquered people. What he found was something very different.

Following a narrow mule trail through the Urubamba Gorge, Bingham was led by a local farmer to a site 2,000 feet above the river at a place the locals called “ancient peak”. Bingham later wrote: “In the dense shadow, hiding in bamboo thickets and tangled vines, could be seen, here and there, walls of white granite ashlars most carefully cut and exquisitely fitted together … would anyone believe what I had found?”

It was late afternoon when I finally had my chance to see Bingham’s lost city for myself. We had just over an hour to roam amidst the ruins, still burdened by our packs and trail-worn clothing. Day trippers who came up on one of the rail services from Cuzco had already started their return, providing us the chance to contemplate the mysterious wonder of this place nearly alone as the day neared its end. As I sat on the terraced slopes watching the remaining tourists head for the buses that would take them down to the tourist hub of Aguas Calientes, I could picture thousands of Inca scurrying about doing daily chores and worshiping their gods in the most picturesque small town on earth.

After enjoying a hot shower and night in a comfortable bed, we woke early the next morning and took a bus back up the steep switchbacks from Aguas Calientes. We were among the first to enter the sanctuary for our guided tour. The labyrinth of ruins was again shrouded in fog. The famous towering emerald spire of Huayna Picchu was barely visible through the windows and doorways of the greatest archaeological discovery of modern times. We listened to Narcico share stories of solar calendars and secret rituals. By mid-morning the day trippers began to arrive and the clouds slowly lifted, revealing the valley below.

A century has passed since Hiram Bingham introduced the world to Machu Picchu. Today, thousands of tourists are transported to the once forgotten city on a luxury train that bears his name. A new city has emerged to support a growing tourism industry along the banks of the Urubamba River near where he camped, and resilient descendants of the Inca continue to live simply in the Peruvian highlands only marginally connected to the national economy.

I came to Peru to walk in the footsteps of the Inca to a lost world with a romantic and mysterious past. Through this journey I learned that the Inca culture hasn’t vanished under a jungle canopy or been destroyed by marauding invaders. While their ancient customs and rituals have blended with new ideas and new gods from different places, the Inca spirit lives in villages near Cuzco and throughout the Sacred Valley. As we piece together the history of Machu Picchu, it only raises more questions about the people who built it and who still call it their home.