Story by Kathleen Pokrud

Photos by Jenny Chan and Teresa Biesty

“Egypt is the gift of the Nile,” declared the Greek historian Herodotus. The Nile Valley is the birthplace of one of the oldest and wealthiest civilisations the world has ever known. I sat down with Madame Omneya El Kouny, spouse of HE Moustapha El Kouny, ambassador of the Arab Republic of Egypt to the Kingdom of Thailand, to learn about Egyptian culinary history.

For more than 7,000 years, the Nile Valley has provided Egypt with fertile soil and water for irrigation, and a main reason behind the country’s cuisine. Madame Omneya explained, “Egypt represents around 3000 years of history and its food traditions, ever expanding crops and cooking techniques. The information that has been recorded is about raw ingredients, but almost nothing about the earliest preparation methods or dishes is known as no written menus survived from ancient Egypt. Bread was the main staple used in many ritual and funerary traditions. Hundreds of loaves of bread have actually survived from ancient Egypt as they were placed in tombs for the deceased to consume. Ancient Egyptians mainly used two types of cereals, emmer wheat and barley to make their bread.”

Madame Omneya elaborated; “Vegetables and legumes were important accompaniments to the breads. Onions, especially spring onions, were always part of standard tomb offerings. Lettuce and Egyptian cucumber were also staples often shown in paintings of offerings. Pulses such as lentils were also widely consumed. Lentils would have been either consumed before or after processed to remove their brown coats and served orange. There is no evidence of how they was consumed. One of the unique components in ancient Egyptian food is the tiger nut, a member of the papyrus family. Its roots are delicious, eaten fresh, dried or roasted.”

She then added, “Fruits were a very common element of funerary offerings. Dates were consumed fresh or dried. Grapes were the most popular fruit and came in several colours and varieties. They were not only a tasty, refreshing fruit, but could also be dried for storage or used to add sweetness to cakes and breads. Pomegranates were delicious to eat as well as a succulent juice, which may have been left to ferment to produce an ancient Egyptian wine. The beautiful fruit of the pomegranate was often used in decorative motifs appearing in jewellery. Watermelons and other types of melons were also known in ancient Egypt. Several fruits once popular among the ancient Egyptians, however, are no longer known.”

On the subject of meat consumption, Madame Omneya explained, “Beef was, like today, the most prized source of meat, followed by goat and pork. Pigs were consumed, although on occasion, prohibited for priests. Crocodiles were some of the unusual wild animals consumed.

“Duck, geese, and quail were eaten in addition to wild birds. A hundred species of Nile fish were eaten, including tilapia, catfish and Nile perch, which are consumed up to today. Spices such as coriander, cumin, dill and fenugreek were available, often imported from other countries in the Near East or Africa.”

Madame Omneya highlighted the use of honey in ancient Egypt. “Honey was a highly expensive commodity only accessible to the wealthy as many believed it was created from the god Ra’s tears that turned into bees. Not only was it used as a sweetener in foods and probably drinks, it was also appreciated for its medicinal and antibacterial properties.”

On Egyptian culinary culture, she commented, “Food trends in Egypt mirror the diverse influences from around the Mediterranean. During the Graeco-Roman period in Egypt, food defined classes, standards of living and people’s wellbeing. The main diet available consisted of grains, pulses, oil, and beer. Grain provided the carbohydrates and vitamins, pulses for protein, oil for unsaturated fat, and water and beer giving the liquid the body requires. Vegetables and fruit were certainly added, wherever they grew; meat and fish were reserved for the festivals of the gods and very special days, like weddings, birthdays and funerals.

“Beans and lentils were the most popular pulses; other popular vegetables included cabbage, garlic, lettuce, chickpeas, onions, beets, gourds, radishes, cucumbers, leeks and turnips. Dates, which grew in large quantities all over Egypt, were the most popular fruit; figs, nuts, pomegranates and apples were less common, as were peaches, melons and lemons. The most common oil in ancient Egypt was pressed from radish and sesame seeds. The Greeks brought with them olive oil, which eventually became predominant. It remained more expensive through the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, but gained wider popularity with time.

“Beer — beside water of course — was the main drink in ancient Egypt. It was made from bread with a fermenting substance added. The Greeks were not familiar with this drink. The cultivation of wine was known in Pharaonic Egypt, but it popularity came with the Greek-speaking settlers from around the Mediterranean and increased over the centuries.

“The Islamic conquest of Egypt in 641 CE played a major role in adding to its already abundant harvests by introducing important crops such as rice, sugarcane and citrus fruits. The fertile lands along the Nile guaranteed favourable conditions for growing these migrant crops.

“Besides crops, the Islamic conquest brought diversity of another sort to the region. Egypt’s Arab Muslim and Coptic populations were augmented as the country became a cultural magnet and haven for the surrounding regions and peoples of multiple nationalities and ethnicities, particularly after the attacks of the Mongols in western Asia.

“Egypt gradually became home to Turks, Kurds, Moroccans, Sudanese, Persians, Iraqis and many more. This multiplicity enriched the local cuisine. Trade with the surrounding regions, especially the Levant, was also quite active. Products imported from that region included walnuts, pistachios, hazelnuts, apples, quinces and pears. Egypt, meanwhile, exported to the countries surrounding the Mediterranean its surplus of local products such as salt-cured fish; ḥalloumi cheese; oils radish and turnip seeds; pulses and refined sugar. Importation of spices and other aromatics from India and beyond continued for centuries by prosperous Egyptian merchants.

“The Roman Empire drew much of its food supply from Egypt. Centuries later, the Ottoman Empire grew perhaps up to a quarter of its food supplies in Egypt’s rich soils. For millennia, Egypt served as the proverbial breadbasket of the Mediterranean.”

As our interview drew to a close, Madame Omneya shared, “The twentieth century saw some of the most drastic changes in Egyptian food habits. The end of it largely lost many food traditions present at the start of the century. During the first half of the century, royalty and nobility continued to enjoy a largely Ottoman and European-style diet.

“The annual Nile floods, previously at the heart of Egyptian agriculture, were curbed in the twentieth century, first with the Old Aswan Dam, completed in 1902, and then the High Dam in 1960. No longer were Egyptian peasants at the mercy of the floods that long determined their seasonal diets, but new factors started playing pivotal roles in food choice. These included new levels of social mobility, technology, governmental initiatives and media influences. What is fascinating is how traditional Egyptian foods are often very healthy and with a high nutritional value. These include the many sprouted foods such as fenugreek and roasted and germinated fava beans.”

Egypt’s national dish

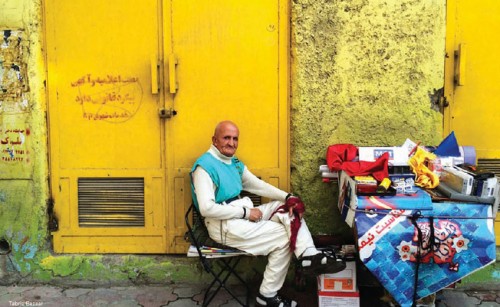

Koshary, kushari or koshari is Egypt's national dish and a widely popular street food. It is a traditional Egyptian staple, mixing pasta, Egyptian fried rice, vermicelli and brown lentils, topped with a zesty tomato sauce and garlic vinegar and garnished with chickpeas and crispy fried onions.

Koshary was sold on food carts in its early years and later introduced to restaurants. This dish is widely popular among workers and laborers and well-suited to mass catering events such as conferences. It can be prepared at home and served at roadside stalls and restaurants all over Egypt. Some restaurants specialize in koshary to the exclusion of other dishes while others feature it as one item among many. Traditionally, koshary does not contain any animal products. It can be considered vegan as long as it’s fried with vegetable oil.

Koshir is a breakfast dish consisting of lentils, wheat, chickpeas, garlic and onions cooked together in clay pots. In the Egyptian Book of Genesis, the Ancient Egyptian term "Koshir" meant "Food of the rites of the Gods". The word is not related to the Jewish dietary laws known as Kosher. A priest from Heliopolis described it as a food to eat after fasting on the 11th day of Pachons, a month in the ancient Egyptian calendar. It consists of fried onions, lentils, rice, macaroni and a red sauce. It is somewhat related to Mediterranean cuisine, but the Egyptian dish has different ingredients and flavours, especially with the local Egyptian lemon sauce that gives it the unique taste for which the dish is popular.

Falafel is a popular vegan Egyptian dish. Deep fried balls are made from ground Fava beans, fresh herbs, onions, garlic and spices. Egyptian cooking also incorporates many kinds of leafy greens full of antioxidants such as the green leaves in taro meal or other greens considered weeds by some farmers such as Swiss chard, purslane and mallow leaves. The twentieth century saw some of the most drastic changes in Egyptian food habits. The end of it largely lost many food traditions present at the start of the century. During the first half of the century, royalty and nobility continued to enjoy a largely Ottoman and European-style diet.”

What is fascinating is how traditional Egyptian foods are often very healthy and with a high nutritional value. These include the many sprouted foods such as fenugreek and roasted and germinated fava beans.