The towering peak of la Cumbre was hidden behind a vaporous cloak of dense fog, intensifying the mysterious stillness as our panga shuttled us towards an unearthly landscape. We carefully made our way across the slick hardened lava, taking our rst tentative steps along the rugged coastline of Fernandina. In the cracks and shadows where the volcano meets the sea, some of the strangest creatures imaginable took notice of our presence. We had entered a prehistoric world where amphibious dragon lair and exotic life clings to the sharp edge of an unforgiving home.

As the night-time chill began to yield to the equatorial sun, Fernandina awakened and the world’s only sea-lizards revealed themselves through subtle movements and periodic spurts to clear salt from their nostrils. The rocks were spitting. Hundreds of spiny marine iguana draped the barren earth as we followed a marked trail over elds of swirling pahoehoe lava, punctuated by the occasional pioneering lava cactus.

Fernandina is the youngest and most inhospitable of the Galápagos Islands. It is an active volcanic wasteland that grows at the very heart of a geothermal hot spot, straddling a complex series of tectonic plates and underwater ridges. Over millions of years, primordial forces have spewed a superheated magma, raising the Galápagos platform and exposing the visible summits of undersea volcanoes.

From the oldest in the east to the youngest in the west, the 13 major islands and over 100 smaller islets and rocks of the archipelago are scattered over 320 kilometres, moving southeast with the shifting oceanic plates at a rate of four centimetres a year. This slow and sometimes violent journey along a geologic conveyor belt is evidence of a living planet. The Galápagos Islands are still changing, still evolving and still adapting to unpredictable forces now witnessed and directly in uenced by a growing number of curious travellers from around the world.

As we neared Fernandina's north shore of Punta Espinosa, I stopped to photograph young sea lions frolicking in a small inlet and ightless cormorant warming their wings on the rocky shore. As the late morning sun broke through the haze, I could nally see Isabela, Fernandina’s giant island neighbour to the east, and the looming summit of La Cumbre. Everywhere, it seemed, the once motionless iguana were repositioning themselves for maximum exposure to the warming rays of the rising sun or scurrying into the water for a breakfast of algae. The increasingly intense light exaggerated the already brilliant colours of sally lightfoot crab, framed against a pallet of black, as they ducked into small ssures and holes to avoid the advancing parade of tourists.

We snorkelled off the coast of Isabela with sea lions, turtles and Galápagos penguin in the protected Tagus Cove, and travelled the open ocean in darkness and at rst light found ourselves on the doorstep of a new and fascinating island world.

By the time a young 26-year-old Charles Darwin visited the Galápagos in 1835, there had been three centuries of human interaction with the islands. The bizarre wildlife now shared their geologic oasis with pirates, whalers, fur sealers, convicts and castaways, but they had never been successfully settled. Although several non-endemic species like goats and rats had been introduced to the islands, Darwin found a nearly intact ecosystem largely unaffected by the hand of man. Not only was there an abundance of unique species, but identi able variation from island to island. He and others later theorized that the very diversity of species and subspecies illustrated how populations adapted to ecological niches.

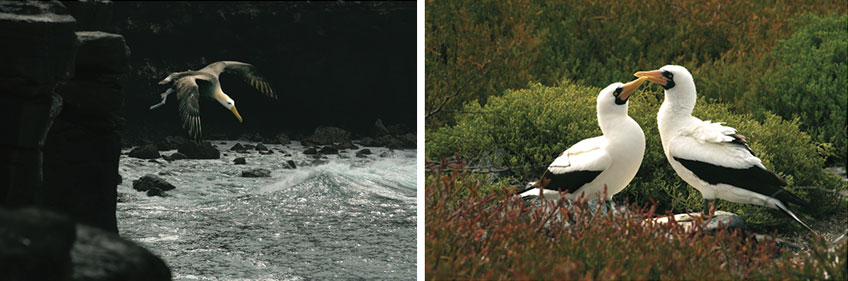

On most islands of the Galápagos today, visitors follow a narrow band of marked trails where they discover the best known creatures of the coast, prohibited from personal inland exploration. On the weather-worn and lightly visited southernmost island of Española, the tourist trail leads past blue-footed boobies, edgling waved albatross and the bleached bones of earlier generations to a stunning vista of soaring seabirds and ragged coastline. Almost the entire world population of waved albatross live and breed on Española. They follow the shifting currents of the Humboldt and spend nearly half the year at sea feeding on squid. They return to Española in April to mate and raise their young. By December, they again take to the air and follow the Humboldt Current to their feeding grounds off the costs of Peru and Chile.

I experienced a raw and intimate connection to a place where the cycles of life and death are not hidden by walls of civilization, but experienced, naked and authentic, just metres and moments away. I watched as a suckling newborn sea lion pup drifted in and out of a peaceful sleep as the click of my camera introduced a modern sound to an ancient world. I was captivated by the inquisitive stare of a young waved albatross and the paternal dominance exhibited by a male sea lion patrolling his small section of sandy beach on an island speck in a massive ocean. A short distance away the broken wing of a struggling seabird foretold a certain death while an enthusiastic booby couple began their courtship with a silly display of affection. I cherished the eeting moments of simple observation knowing that species have come and gone, adapted and died, in a constant chain of interconnected events for millions of years without human witness.

Annual tourism has grown from 40,000 visitors to over 140,000 in just the past 15 years, however. This worldwide interest has also swelled the resident population to over 30,000, accompanied by new predator populations of dogs and cats. New and potentially fatal diseases have arrived with humans and their pets. There is a now-constant ow of food, energy and resources to support this permanent colonization.

The place that inspired centuries of investigation, research and re ection into the very nature of our existence, may ultimately be destroyed by our very presence. The Galápagos is a unique and special world protected for millennia by its isolation. But now the islands are no longer feared, no longer a secret to a modern world with jet aircraft and the wealth to travel. Sometimes by intent, more often through ignorance, we are destroyers of worlds.